|

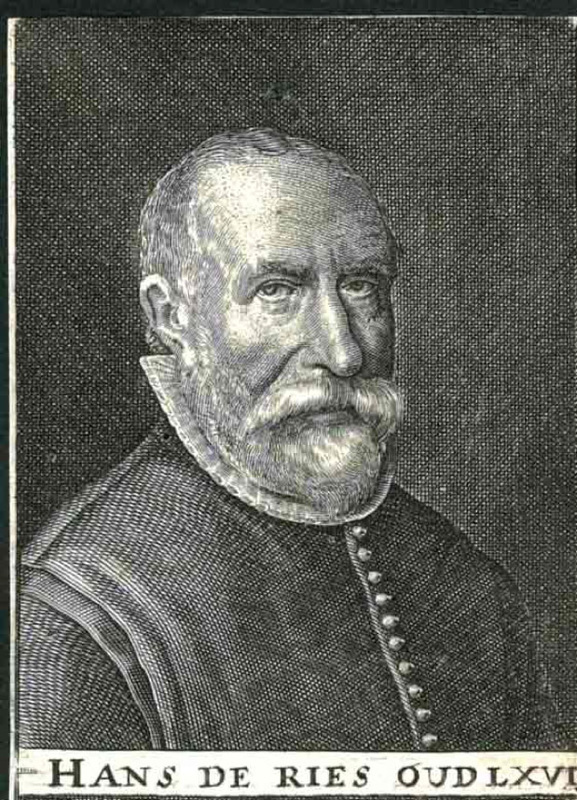

Hans de Ries was a Catholic priest in Antwerp, Belgium when he and another cleric, Hans Bret were arrested and tried for teaching Anabaptism. Hans De Ries was found innocent but Bret was burned at the stake in the market square. De Ries promptly fled to central Holland where he was appointed pastor in a Protestant Dutch Reformed congregation. Within a few months he resigned his post. He had given one sermon after another on nonresistance and yet the women and men brought their daggers and swords into the church. He quickly left for the city of Alkmaar north of Amsterdam. In Alkmaar, he was he was rebaptized as an adult and began his long ministry among Mennonites. After serving for about a year, he was began a nomadic ministry across Holland, North Germany and far into what today is Poland. Eventually he also traveled to South Germany and Switzerland to train pastors and mediate congregational conflicts. After 16 years on the road, he returned to Alkmaar where he was pastor of the Mennonite church for the nearly forty years.

On account of his travels, de Ries knew more about the entire Mennonite church than any other pastor. He recognized the diversity that had been with the Anabaptist movement from the beginning and still continued into his day. There were significant differences in doctrine, worship practices, urban versus rural vocations, clothing styles, foods, languages, acceptable music for worship and even a preference for spoken versus silent prayer. In the Netherlands there were also great divisions. The Flemish in the south emphasized the importance of simple dress as a symbol of separation from society. The Frisians in the north endlessly debated nuances in doctrine while the Collegiants toward the west sought a rational, universal and abstract faith that transcended traditional boundaries. For example, the Collegiants welcomed the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza into their circles. Finally, de Ries’s association of congregations, the Waterlanders, valued artistic expression and social action. This was the Golden Age in Holland and many artists, including Rembrandt, attended Waterlander services. Many artists, academics, physicians, poets and were active in Mennonite churches during that era. The religious and cultural differences among Mennonites did not discourage de Ries from developing a vision for a unified Mennonite church. Instead of reconciling these differences, he side-stepped them and emphasized the importance of beginning common ministries that no one congregation could undertake on its own. Under his leadership the differing Anabaptist groups established homes for orphans, developed programs to aid widows, provided theological institutes for pastors and church leaders and began issuing publications for all interested congregants. As a result some the orphanages and homes for widows are still functioning. Ventures in service, publication and education among Dutch Mennonites have flourished ever since leading, eventually to the 1735 establishment of the first Mennonite seminary in Amsterdam. De Ries’s work attracted the attention of Baptists in England. A large contingent of nearly 150 came to the Netherlands and began discussing a possible merger with Mennonites. When their leader, John Smyth, suddenly passed away about a third of the group returned to England while the rest joined Waterlander Mennonite churches in Western Holland. Also Unitarians (Socinians) from Poland and Moravia as well as Quakers from England traveled to Netherlands as guests of the Collegiants and Waterlanders. De Ries was deeply involved their discussions on doctrinal and religious matters. He was drawn to the Quakers and believed that the light of God resides in the souls of all. C. J. Dyck wrote that de Ries’s work and writings were intentioned to “achieve, rather than enforce consensus” among Mennonites. Even though Mennonites were greatly divided in his time, de Ries never shunned, banned or excommunicated any member, church or group of Mennonite churches. He taught, lived and accepted diversity within the body of Christ. This is remarkable because of the great differences. Again and again he emphasized the need for peace, the necessity to work in harmony with all people and especially for peaceful home life. He admonished the men to show love toward their wives and children and to avoid bringing the tensions and coarseness of the workplace into their homes. De Ries also published extensively. His books and pamphlets on theology comprise about approximately 1,675 written pages. He also wrote a hymnbook for Waterlander churches, more than 200 pages of letters and a massive book on Anabaptist martyrs that later became the core of van Braght’s Martyr’s Mirror. One of the saddest aspects of his legacy is that only one of his publications, A Confession of Faith, has been translated into English. That translation was done in 1962 by C. J. Dyck a former professor at AMBS. With de Ries’s encouragement, Mennonites became central figures in the development of the Dutch Golden Age of art, literature, commerce and education. This visionary man of peace, Hans de Ries, may have much to offer us today as we live with congregational diversity while maintaining unity in service and ministry. Surely the Lord would say of Hans de Ries, “Well done thou good and faithful servant.” Sources:

|

DownloadThe Living Mirror: Archaeology of Our Faith

Archives

December 2018

|

||||||

|

* = login required

|

Visit425 S. Central Park Blvd.

Chicago, IL 60624 |

Contact |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed