|

The posts in this blog, "Archaeology of our Faith," are the stories of lesser-known Anabaptists, a project of CCMC member Lauren Friesen.

John F. Funk was a man of vision and action. He spent his early years in Eastern Pennsylvania and attended the Freeland Institute to become a high school teacher. After teaching two years, he joined his brother-in-law Jacob Beidler and they purchased a sawmill in Chicago. This venture was highly successful and soon they were also making newsprint and they invested in a small printing company. The printing press was useful and enabled them to work with the young evangelist Dwight L. Moody. It was Moody who convinced Funk, who was still only in his 20s, to give his life to God and serve the church.

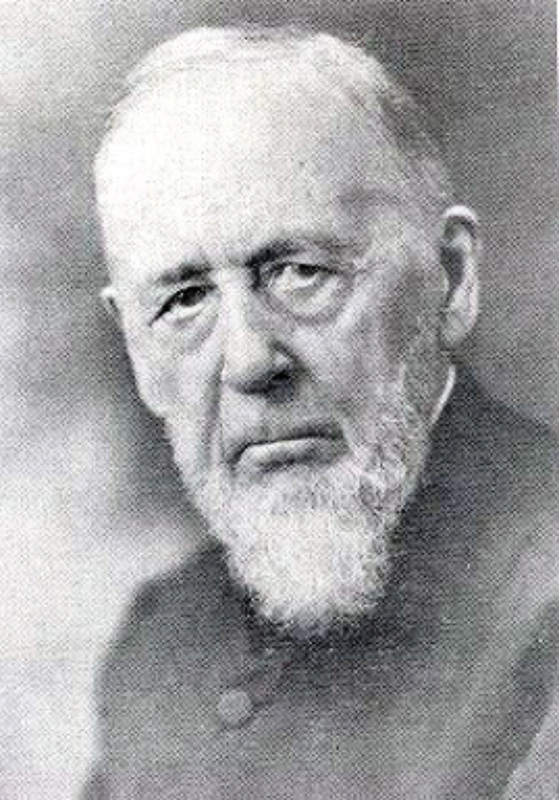

Funk accepted the challenge, returned to his home church in Pennsylvania, was baptized, married Salome Kratz, and moved back to Chicago. He went back to his former job but he added a new dimension: a weekly newspaper, The Herald of Truth. The goal of the paper was to unify all Mennonites in North America. In 1863, during the American Civil War he published a book titled War: Is it Evil or is it Good? With the success of this work and the continued encouragement from Dwight L. Moody, he devoted more time to publishing and writing. At the age of 32, Funk sold his portion of the Chicago business and moved to Elkhart Indiana. There he established the first Mennonite Publishing office in North America and his newspaper served as the flagship of the firm. He also published Mennonite books including the massive Martyrs Mirror and The Works of Menno Simons. Funk formed a loosely organized mutual aid society which took on the task of aiding Russian Mennonite immigrants in the 1870s. Funk traveled with the first group to Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota and Minnesota to scout out prospects for settlements. Furthermore, he raised funds to assist with relocating many who arrived with inadequate resources. In total, they assisted more than 20,000 immigrants over a four year period. In 1893 he returned to Chicago to attend the Columbian Exposition. Funk was captivated by the art museum and its contents but he didn’t care for the ethnographic exhibits which, in his estimation, had far too many naked people. Funk had an eye for talent and in short succession hired gifted, young men (J. S. Coffman, John Horsch, H. A. Mumaw, Noah Kolb, Daniel Kaufman and G. L. Bender) who worked in his publishing firm. Together they formed the nationwide Mennonite Church General Conference which met for the first time in 1902. This organization established active committees that formed

Unifying all the Mennonites was far more difficult than he had ever imaged. Funk became discouraged when, as the decades passed, instead of unity, he witnessed new schisms. Troubles increased for Funk when the young assistants no longer passively accepted his stringent management methods. Most of his staff resigned en masse in 1908 and moved to Scottdale, Pennsylvania where they started the Mennonite Publishing House and a new magazine The Gospel Herald. His own publishing house was floundering and he had to declare bankruptcy. Even though that was a personal failure, of sorts, the ventures he began became highly successful: The mission board, Mennonite mutual aid, committee for orphans and youth, the service committee, and the college all remained in Indiana where they are still to this day. John F. Funk was a man of vision who was able to realize most of his dreams for a more unifed and effective church. Reader: Surely the Lord would say of John F. Funk All: Well done thou good and faithful servant. Sources:

Born in Iowa, raised in Newton, Kansas where he had his early education in public schools and Bethel College. His family was deeply rooted in the Mennonite world of the late 1800s in the Newton area. Krehbiel’s father was a carriage maker and one of the founders of Bethel College. To his father’s dismay, all Albert wanted to do was draw and paint. But then as a practical businessman, he had Albert paint the ornamental flourishes on the high-end carriages for notables of the day.

When Frederick Richardson, president of the Art Institute of Chicago, saw Krehbiel’s work he offered him a five year scholarship to complete his education and spend a subsequent year as a studio assistant in painting. After completing those five years, Albert received a fellowship to study at the Academie Julian in Paris. At the Academie Julian he developed close connections with artists of the time including Auguste Rodin, Andre Gide and Jean-Paul Laurens. During his time at the Academie Julian, he won a record number of four gold medals for his impressionistic paintings. And of his works was selected for permanent exhibition at the Academie. Just before his return to the United States in 1905 he also won the Prix de Rome award which was the highest European honor bestowed upon a student painter. After his return to America, he would join the faculty at the Art Institute in Chicago where he taught painting until his final years. But his energies were not limited to the Art Institute. He devoted four years to painting the murals in the State of Illinois Supreme Court Building in Springfield, Illinois. After those murals were complete he returned full time to impressionist painting. Later he would become the primary interior designer for the immigrant architect Mies van der Rohe for his early buildings, including innovative S. R. Crown Hall on the Illinois Institute of Technology campus in Chicago. His wife, Dulah Marie Evans, was also an artist who taught part time at the Art Institute. Together they spent summers in Saugatuck, Michigan where they painted landscapes and began the Summer Art Institute which is still functioning today. And of course, Chicago weather got the best of them and early in their marriage spent their summers in Santa Fe, New Mexico where they worked with and exhibited art with many other noted artists. After their son Evan was born, they spent summers teaching art in Saugatuck, Michigan. Krehbeil’s work is in many private collections today and also in major museums. The museums, and I will only list a few, include The Louvre in Paris, The Smithsonian, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the British Museum in London, San Francisco Museum of Art, University of Michigan Art Museum and of course the Art Institute in in Chicago. He completed close to thirty paintings a year during this forty five years as a professional artist. And please note, he was also teaching full time during those same decades. Albert’s professional interests and career took him far away from his Mennonite roots in Kansas, but whenever he and his family made their annual pilgrimage to New Mexico, they would visit relatives in Kansas and often provide a guest lectures on art at Bethel College. He remained close to his brothers and many of their letters have been preserved in the Bethel Archives. Finally, Albert Krehbiel was a good writer and penned this oft quoted statement, "People cannot stop growing, nor can they continue making new things merely in imitation of what has been done. Each age must have its new tempo, its own plan and pattern, and must express itself soundly in the terms of that pattern and in the measure of that tempo." Albert Krehbiel retired on June 29, 1945 at age 72 and later that same day, as he and his son were packing for a trip visit relatives in Newton, Kansas, he passed away. Reader: Surely the Lord would say of Albert Krehbiel All: Well done, thou good and faithful servant. Sources:

The historian Robert Krieder begins his article on Vincent Harding by stating “For one bright and shining hour there was in Chicago a congregational Camelot, the interracial Woodlawn Mennonite Church, an innovative model for Mennonites … in the city.” Vincent Harding and Delton Franz were co-pastors of this church located on 46th and South Woodlawn. They were the first interracial Mennonite pastoral team on record. During this time, Reverend Harding traveled extensively as a guest preacher and lecturer in many Mennonite churches and colleges.

Together, the Reverends Harding and Franz began a series of workshops and seminars for pastors that focused on race and reconciliation. In 1960, Harding married Rosemarie Freeney whose parents were active members at Bethel Mennonite Church in Chicago. A year later, Mennonite Central Committee encouraged the Hardings to move to Atlanta to organize voluntary service efforts and manage a guest house. Vincent and Rosemarie lived on the same block as Martin and Coretta Scott King which resulted in personal friendships and professional collaborations. Vincent would eventually write some of Dr. King’s most stirring speeches including the famous anti-war sermon “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” delivered at Riverside Memorial Church in New York City. In 1965 Harding completed his dissertation at the University of Chicago and was hired by Spellman College as the chair of their history department. This academic appointment, coupled with his skills as a writer brought new opportunities to Dr. Harding. He would author ten scholarly works including the award winning text on African American history There is a River. He collaborated with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on the soul searching work Where do we Go from Here? He also challenged American readers to consider the contribution African Americans have made to our national identity in We Changed the World: African Americans 1945-1970. The underlying thesis in all of his works might be summed up as: American history cannot be understood without comprehending the Black struggle for social justice, economic equality and religious vitality. Dr. Harding’s journey with Mennonites was not a smooth one. He gave a stirring sermon entitled “The Beggers are Rising: where are the saints?” at the 1967 Mennonite World Conference in Amsterdam. Shortly after that lecture, he appealed to Mennonites to become more committed to urban ministries with his provocative poem “Light in the Asphalt Jungle.” When these prophetic and provocative works were openly criticized by a few key Mennonite leaders, Harding began to distance himself from the Mennonite fold. He summed up his views in this manner, “We (Mennonites) have loudly preached nonconformity to the ways of the world, and yet we have so often been slavishly and silently conformed to the American attitudes on race and segregation.” Mennonites, in his eyes, were too slow and late in discovering that without justice, there is no peace. In 1981 he was hired by Iliff School of Theology in Denver which became his academic home from that year onward. After his retirement in 2004 Dr. Harding renewed his involvement with Mennonites and provided workshops and lectures in churches, colleges and seminaries. Leader: Surely the Lord would say of Dr. Vincent Gordon Harding, All: Well done thou good and faithful servant. Sources:

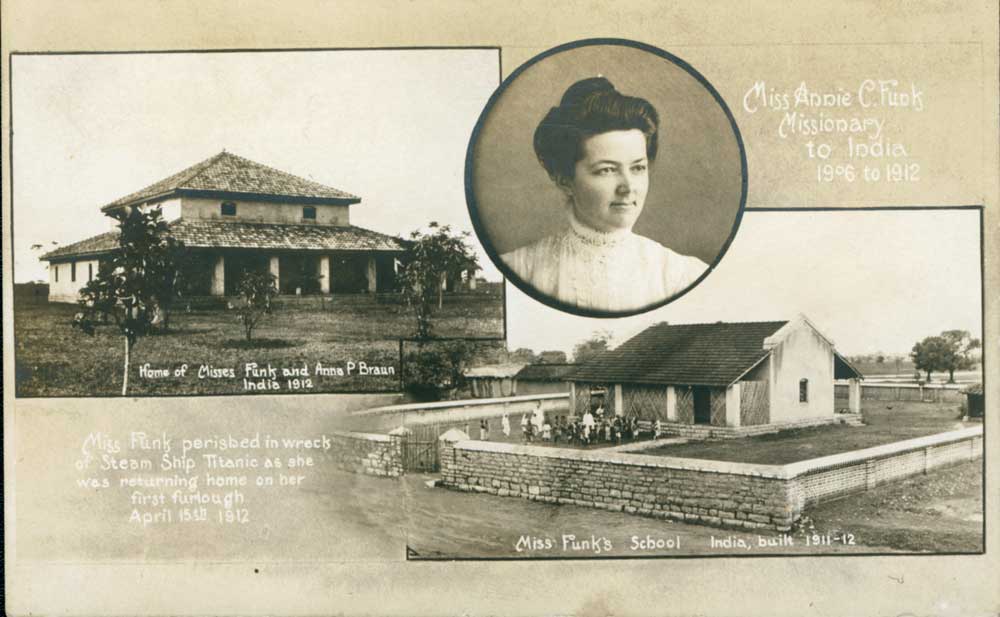

It is a new year and a time to celebrate new beginnings. One of those new developments began a little over a hundred years ago and today some still think of it as a new: the ordination of women. It happened this way: Annie Clemmer Funk became the first Mennonite woman in North America to receive ordination.

Pastor Samuel N. Grubb ordained Ms. Funk in the Hereford Mennonite Church in Bally, Pennsylvania in 1906. Within 5 years, 5 more women would be ordained to serve in a variety of Mennonite ministries as pastors, missionaries and Deaconesses. These included Frieda Kaufman, Catherine Voth, Ida Epp and Martha Richert who were ordained in Kansas in 1908. And in 1911 Ann Jemima Allebach was ordained also by Reverend Grubb at First Mennonite Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Prior to 1906, only Dutch Mennonites ordained women. Annie Funk grew up in Bucks country Pennsylvania and received teacher training at West Chester State Normal School and then continued her education in Massachusetts as the Northfield Institute. She began her professional work as a teacher in all Black schools in Chattanooga, Tennessee and Paterson, New Jersey. After she learned of the lack of education for women in India, especially children born into poverty, she made a momentous decision. Annie Funk declared her interest in joining missionary P. A. Penner and his wife Martha Richert Penner and become a teacher and start a school for girls in Jangjir, India. Annie’s decision faced opposition from the beginning. The Mission board was not interested in sending an unmarried woman to India. But after a lengthy interview the board approved the appointment. Following the board’s decision to sponsor her as a missionary teacher, Ms. Funk was ordained in her home church in Bally, Pennsylvania. After arriving in India, it didn’t take long for this energetic and talented leader to establish a school for girls. In 1907, 18 girls were enrolled and the school expanded over the years to accommodate 150 students. The school grew rapidly under Annie’s leadership and continued to serve the poor and children of leprosy victims. In 1912, the Pennsylvania Mission Board sent her an ominous telegram. Her mother was seriously ill and requested that Annie return. The tickets arrived and within a few days, Ms. Funk was on a steamer headed for England where she needed to change to another liner for the voyage to America. When the ship arrived in England, her passage to America was delayed due to a strike by the ship’s crew. The travel agency, Thomas S. Cook, recommended she change to another liner, a new ship that would depart the next day on its maiden voyage. And that is why she boarded the Titanic and headed out to sea. After the Titanic hit the iceberg, Annie waited in line for a life-boat but, according to eye witnesses, gave up her place on a boat to a mother with small children. Friends and family later agreed that she died the way she lived, “sacrificing her life so that others might live.” The girls school in India continued and was renamed the Annie C. Funk Memorial School. Over the years, this school educated thousands of women who went on to become teachers, nurses, doctors, village and religious leaders. Surely the Lord would say of Annie Funk, well done thou good and faithful servant. Photo source: GAMEO Sources:

Elvera Voth (1923 – ) Elvera Voth (1923 – ) “Elvera Voth – risk taker extraordinaire!” Thus read the headline in the International Journal of Music. And what a risk taker she has been. Her musical training began in Goessel, Kansas where she was born and raised. In college and graduate school she earned degrees in music and choral conducting. A series of academic appointments followed one after another: Freeman Junior College, Bethel College and Alaska Community College in Anchorage. When we look beyond these basic details, a highly complex persona emerges. Early in her academic career she campaigned for equal pay for equal work. After a series of intense conversations with administrators, these academic institutions eventually adopted such a policy. But Ms. Voth was a dynamo that could not be confined to a classroom. In Alaska she was the founding director for the Anchorage Community Chorus, the annual Basic Bach Festival with the guest conductor Robert Shaw, the Anchorage Lyric Opera and the Anchorage Boys Choir. Each summer she organized and conducted an outdoor choral festival with the theme “Music to Match Our Mountains.” The Anchorage Symphony Performing Arts Center recently named their rehearsal rooms and performance spaces the Elvera Voth Hall. She organized the campaign to have the Alaska legislature earmark 1% of all state income tax revenues for the arts. Her efforts benefited all the arts programs across many cultures and communities in Alaska. In 1991 Elvera announced her retirement but according to observers, her major contribution was just beginning. She became the choral conductor and vocal instructor for the East Hill and West Hill singers in Lansing, Kansas. East Hill and West Hill are the names for the minimum and maximum security wings of the Kansas State Penitentiary. Although she had many skeptics at the beginning, it became a full-fledged arts program behind the walls of the Kansas Penitentiary. The Wichita Eagle headlined this venture, “Helping Music Find Lost Souls.” Within a few years, her choral groups were performing in communities across Kansas. When the conductor Robert Shaw heard of this project he came to Bethel College in Kansas and conducted a benefit concert to raise funds for Voth’s music in prisons programs. Mary Cohen writing for the International Journal of Choral Singing stated, “Shaw and Voth shared a passion for social justice and musical excellence and the belief that choral singing could be a vehicle to transform lives and prompt social change.” Elvera expanded the program to include other arts: poetry, theatre and photography. At one time well over half of the prisoners in the Penitentiary were in one arts program or another. Due to declining health, she concluded her prison work in 2010. In 2014 she was elected to the Alaska Women’s Hall of Fame. When a reporter asked why, why spend your retirement years working with society’s cast-aways, she replied, “I just didn’t want to give them one more failure in life. Why keep everybody at arm’s length? They are coming home sooner or later. Do you want them to come back with hate in their eyes or hope in their hearts?” Leader: Surely the Lord would say of Elvera Voth All: Well done thou good and faithful servant. Sources:

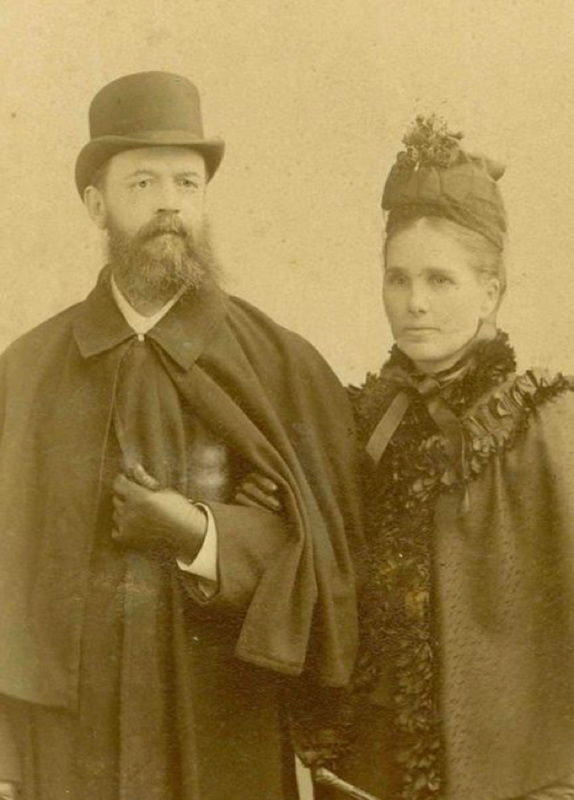

Peter M. Friesen was born in the Molotschna Colony in South Russia in 1849. He graduated from Central High School (Zentralschule) in Halbstadt, Molotschna and completed his university education with studies in Basel, Switzerland and Moscow, Russia. Peter was baptized in the Mennonite Brethren church at age 16 but during his university years drifted away from Christianity in general and Mennonites in particular.

He and his wife, Susanna Fast, lived in Moscow until he was 35 years old when the Central High School in Halbstadt asked him to become their principal. He taught in both German and Russian with equal competence and revised their curriculum to include a teacher training institute. The Mennonite Brethren in Halbstadt without hesitation ordained Peter as one of the pastors. The next 20 years were very active ones for this visionary educator: he wrote the first Confession of Faith for the Mennonite Brethren and a one thousand page history of this pietistic Mennonite group. One of his primary goals was to heal the division that had emerged within the Mennonite community. Toward that end, he formed a relief organization called The Allianz and invited all Mennonite, Russian Pietist and Jewish congregations in the area to participate. Acts of compassion, he believed, were more important than dwelling on doctrinal differences. On the issue of baptism, for example, Friesen advocated a pluralistic stance: river baptism as practiced by John the Baptist or sprinkling which the apostle Paul practiced. His views on baptism and a willingness to seek cooperation with neighboring faiths caused quite a stir. Eventually doctrinal principles stood in the way for many and the Allianz folded. The discussions had been intense and in the end, Peter resigned from his teaching position in Molotschna as well as his responsibilities as pastor. Peter and Susanne then moved to Odessa where he served as a chaplain for students attending the university. He was highly successful in attracting students from many backgrounds to his worship services. But students were not the only ones who observed his effectiveness. Local Orthodox priests challenged him to a debate. Afterwards, Russian secret police began following him. Months passed and Peter finally wrote a letter to the Russian Orthodox Bishop clarifying his theological views and pleading for tolerance. Within weeks the secret police ended their surveillance. Under those tense circumstances, Susanna and Peter moved to Sevastopol where he again served as a chaplain for university students. He arrived at the right time; local firebrands had been stoking up anti-Semitic passions for weeks. One night Peter went to the market square where the rallies were held and listened to one harangue after another. Finally, he mounted the platform and gave an hour long impassioned defense of Jews and Judaism. When he finished, the crowd silently dispersed. When his eyesight began to fail, they returned to Molotschna and a few years later Peter passed away following a long illness. But for Susanna and their three surviving children, this was not the end of their ordeal. The troubles of the world followed them to Molotschna: Susanna and two adult children disappeared in the chaos of World War I. One son, Paul, survived the war but spent the remainder of his years in Siberia. And yet, the torch they lit by emphasizing service, education and cooperation continued to live in the hearts of many. Leader: Surely the Lord would say of Peter and Susanna Friesen, All: Well done thou good and faithful servants. Photo Source: GAMEO Sources:

Born in Kentucky, lived in Illinois. No, this bio is not about President Lincoln but someone also worthy of our attention: Roy Buchanan. Mr. Buchanan arrived in Northern Illinois as a destitute teenager looking for work, farming, construction, or anything that might be available. He found work and so much more: a meaningful faith.

Roy worked for Mennonite farmers in Woodford County, Illinois for 6 summers. With the money he saved, bought a farm in Arkansas which flooded and he lost everything. In his despair, returned to Woodford County and resumed his work with Mennonite farmers. As he would write later, “I could feel more at home in this community, enjoying the rich Christian fellowship that was mine…and so I joined the Mennonite Church.” Then World War I broke out and he was drafted. Roy requested Conscience Objector status and was interred in a military camp where he and other CO’s were suffered indignities and maltreatment. In the Camp Leavenworth military camp, he witnessed unspeakable cruelty toward Black conscripts and was deeply troubled by this. For example, one day 35,000 people showed up to witness the hanging of three Black conscripts for a minor infraction. “How cruel and stone-hearted can some people get?” was the question that haunted Roy for the remainder of his days. But that was only the beginning of his experience with human cruelty. Eventually, Judge Harlan Stone learned of Roy’s request for Conscientious Objector status and offered him an agricultural deferment instead. Roy pleaded, instead, for an appointment with the American Friends Service Committee aid the victims of war in Europe. He completed his application to AFSC and three recommendation forms were submitted by the following members of the Metamora Mennonite church: Peter Graber, Andrew Schrock and Sam Unzicker. On the recommendation form Unzicker penned, “(Roy) worked for me for six years and he is one of the most moral young men I have ever met.” AFSC sent him to France where he saw first-hand the devastation of caused by the war. In his memoir he wrote, War is cruel! War is tragic! War can lead to the lowest depths of human degradation. More than fifty years have passed since I spent two years exposed to the tragedies of war and the memories of those months linger indelibly. If I should live to be a thousand years old and my mind stay rational I would not forget those events. After the war, Buchanan returned to Illinois and worked with the Chicago Mennonite Mission located on Union Street (near today’s China town). Then Moody Bible Institute hired him to install their radio station and he was their primary engineer for six years. Then hard times came again. In 1931, during the Depression, he lost his job and, since Mennonites were also facing difficulties, they were unable to assist. Eventually in 1933 he wrote a letter to the American Friends Service Committee outlining his need for a loan of $50 to tide him over through the winter. There is no record of AFSC’s response but we can assume that somehow, somewhere funds were located. After World War II he worked for local newspapers in the Metamora, Illinois area and he began to write his own memoir which covers his work with the Chicago Mennonite Mission, his opposition to war, relief efforts immediately after World War I and employment with Moody radio station in Chicago. Although he worked in a variety of jobs throughout his long life, he considered the years he spent serving the needs of others, especially the victims of war and the poor of Chicago to be his small ‘footprint’ on the world. Surely the Lord would say of Roy Buchanan, well done though good and faithful servant. Sources:

Photo source: Illinois Mennonite Heritage Center, Metamora, Illinois. Aagje Deken (1741-1804) and Bejte Wolff (1738-1804) Aagje Deken and Elizabeth Bekker “Bejte” Wolff were Dutch Mennonite novelists, poets and political activists. Aagje was orphaned at a young age and placed in a Mennonite Collegiant orphanage near Amsterdam. After leaving the orphanage she began her own tea and coffee business while also serving as a domestic in Mennonite homes. She was baptized in the Mennonite Collegiant congregation in Rijnsburg in 1776. Shortly thereafter she published a book of devotional poems that were eventually set to music and became a hymn book for the Haarlem Mennonite Church.

Bejte Wolff was from the Reformed tradition and also wrote devotional poetry. She was married to a pastor who was decades older they lived in a small village near Rotterdam. Bejte’s husband was in ill health and Aagje moved in to assist her with household chores. After he passed away, the two women continued living together and collaborated on many projects. They wrote novels, political essays and poetry which listed both as authors. They were bold in their writing and actions. They called a National Day of Prayer for all Jews, Catholics and Mennonites during a time when they were sharply divided. They frequently appealed for equal citizenship for all religions, for gender equality and justice before the law. They were inseparable in their daily life. Both were active in the Mennonite church in The Hague. They pioneered the epistolary novel form where characters that never spoke face to face but wrote revealing letters to each other. The first was Sarah Burgerhart a novel which explored the life of a woman who was suffering, not for her faith or ideology, but instead due to the inequality women routinely face. The popularity of this novel thrust them into a national spotlight. A Dutch literary tradition was born! Another epistolary novel The History of Sir William Leevend soon followed. Their novels expressed alarm over the moral laxness of the time that victimized women more often than men. Together they wrote volumes of poetry and many were included in a subsequent Dutch Mennonite hymnal. They persistently called on religious and political leaders to focus on their social responsibilities and turn away from doctrinal or dogmatic disputes. They advocated greater reliance on science in the quest for truth. They developed close ties with political causes that advocated equality and justice. When the Prussians invaded The Netherlands, Deken and Wolff fled into exile. They lived in Southern France where they wrote what might be termed an early travel guide, Strolling through Burgundy and another novel The History of Miss Cornelia Wildschut. While in exile, Aagje wrote to the Mennonite Pastor in Haarlem, “I want to help the Mennonite congregation to whom I am dearly attached.” When the Dutch defeated the Prussians, Deken and Wolff returned as heroines who had protested political oppression. The Mennonite historian Michael Driedger (Brock University) asks how we moderns can understand this close relationship. Deken and Wolff shared everything: writing, political action, kitchen, exile, a study and bed. He concludes that since neither ever wrote about their personal relationship we ought to leave it to historical ambiguity. Another historian, Nanne van der Zijpp, stated that they are remembered and admired as much for their relationship as for their writings. Their ten year exile in France exhausted their financial resources. From that time forward, they were assisted by the Mennonite Church in The Hague. Although it is not documented, they were reported to live in one of the Mennonite homes for the aged. Seven years after their return from France, when the both were active in the Mennonite Church, they became ill and died within 9 days of each other. Funeral services were held in the Mennonite Church following which they were buried in the same grave. But death did not have the final word; their poems, hymns and novels are valued by a church and a nation that has embraced them. The city of Amstelveen commissioned a bronze statue in their honor that was installed in 1969. In Amsterdam, there is a street named in their honor. Henry P Krehbiel (1862-1940) was a Mennonite pastor, inventor, historian, publisher, bookstore owner, world traveler, denominational leader, board member for two Mennonite colleges and served one term in the Kansas Legislature. He was also the owner, publisher and editor of the Mennonite Weekly Review.

Henry, also known as H. P., was born in Summerfield, Illinois to Christian and Susanna Ruth Krehbiel. When he turned 16 his parents sent him and his 18 year old brother John to scout out new land in Kansas. The brothers purchased land near Halstead, Kansas and within four years established a wheat farm, built a large house and welcomed their parents and eleven siblings to Kansas. H.P. was not content with farming so at age twenty and without a day in high school, entered Kansas Normal School for Teachers. A year later, a Quaker school quickly hired him as a teacher and he aided his father in the Mennonite Church in Halstead and also with a new school he started: the Halstead Seminary for training preachers, missionaries and Sunday school teachers. He also aided his brothers in organizing a bookstore called the Beehive and, next to it, a hardware store. In his spare time, he invented a continuous sickle for harvesting wheat, which many claimed was more efficient than the McCormick Reaper and, for the seminary library, an apparatus for archiving newspapers. With the encouragement of his family, H.P. enrolled in Oberlin College where 1895 he earned a degree in theology. After completing his degree, the Mennonite Church in Canton, Ohio hired him as their pastor and he was also appointed to the board of directors of Bluffton College. In order to support this new education venture, he began a weekly newspaper Mennonite Review which was also published in German as the Post und Volksblatt. In 1898 he moved back to Kansas with his wife Matilda Kruse and daughter Elva Agnes. There he expanded the family bookstore and renamed it the Herald Book and Publishing Company. His responsibilities with the denomination increased greatly during the early 1900s. He changed the name of the publication to the Mennonite Weekly Review and the German edition was called Der Herald. He served as chair, secretary or treasurer for many committees such as the Western District Mennonite Conference, Mennonite Immigration Bureau, Mennonite Settlers Society and the Bethel College Board of Directors Special Committee for Reorganization. During World War I he chaired a delegation that spent a month in Washington, DC petitioning congressmen, senators and even the Secretary of War on the problems facing conscientious objectors. H.P.s resolve was not dimmed and he set on a nationwide tour of prison camps where Mennonites were confined. He reported his findings to the Secretary of War who then ceased the brutality toward many conscience objectors. It was during that “war to end all wars” that his printing press and bookstore were doused in yellow paint. He quietly cleaned up the mess and continued to publish. After the war, he changed the name of his publication to Mennonite Weekly Review and the German edition to Der Herald. In order to expand his own knowledge of Mennonites, he and his wife visited churches across the United States, Eastern Canada, Europe, the Middle East and India. All along the way he recruited correspondents who would send monthly reports on Mennonite activities in their area. He developed a deep respect for great diversity among Mennonites. Mennonites, he believed, could work together if they followed this dictum: “In essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty.” The essentials for him were pacifism, baptism, education, missions and service for peace. Throughout his long life, he was an advocate for stronger biblical studies programs at our Mennonite colleges or even the possibility of a special school to train pastors and missionaries. The religious controversies of the day, in particular the conservative/modernist crises, also drew his attention. Krehbiel’s position was clear: we should be cautious about both movements. While conservatives claimed to follow the bible, they overlook Jesus’s teachings on peace and pacifism. Although modernists examined biblical history, they also gloss over Jesus’s teachings on peace and pacifism. This issue, nonresistance and pacifism would emerge as his main line of thought. He wrote a number of books and pamphlets but his final one was War, Peace and Amity which outlines his biblical pacifism and a confident vision for contemporary world peace. In 1931, he delivered a speech entitled “What is Pacifism?” at peace conference sponsored by Quakers, Mennonites and Church of the Brethren. Surely the Lord would say of H. P. Krehbiel, well done thou good and faithful servant. Sources:

|

DownloadThe Living Mirror: Archaeology of Our Faith

Archives

December 2018

|

||||||

|

* = login required

|

Visit425 S. Central Park Blvd.

Chicago, IL 60624 |

Contact |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed